Live An Extraordinary Life

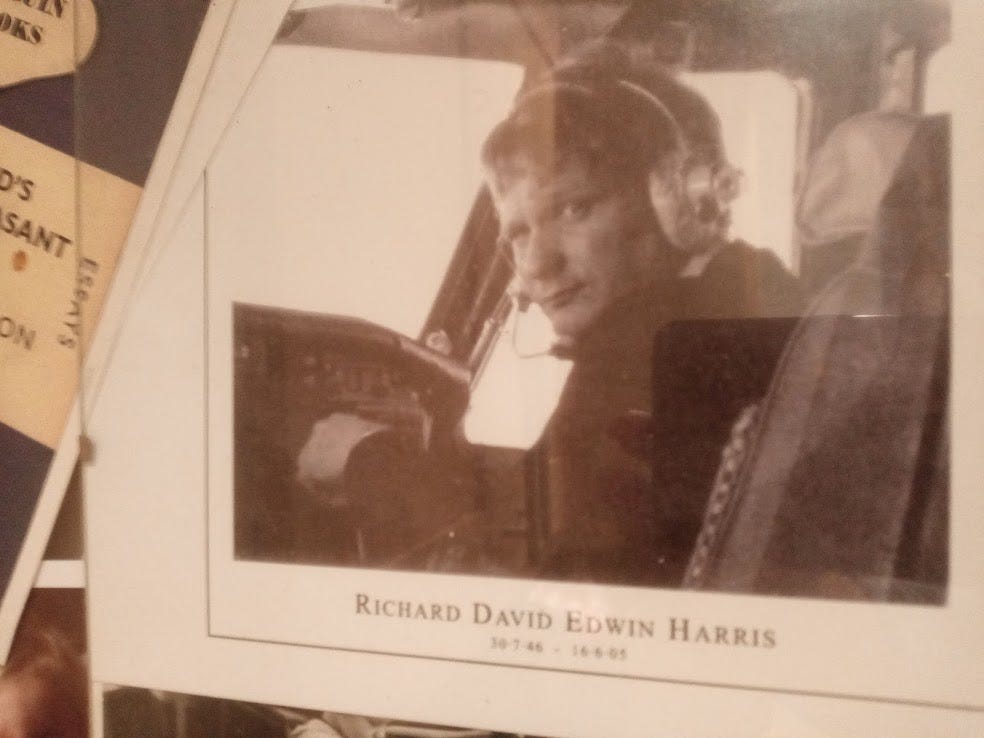

Some of my Twitter pals will have heard this story, but it bears retelling. I loved my Dad. Not in a weird way. He was an intellectual Titan, a pilot who flew aid across the world in every plane, and an aviation disaster expert including Concorde and 9/11, but he was not an easy man, in any way.

I was working in Palm Beach and phoning home on calling cards - remember those! - and Dad said he wasn’t feeling great. Which was unlike him. He was always on form. ‘I’m really not feeling good.’ When I got back our GP whose children I used to babysit and who had been authorised to tell me everything called me and said, ‘Lucy, your father has cancer, and I do not know where it is, right now without an MRI, but from his bloods I do not know how he is still walking around’.

So we got an MRI and yep, the full dog’s breakfast of cancer. The hourglass had turned and the sand was running. Outwardly, he looked like a fit man in his fifties, inside, it was like a bag of sprouts, but cancer.

I quit my job and hared home to Lincolnshire. Dad was unspeakably brave. He wanted to read the diaries of Samuel Pepys, because he never had, and I had to tell him he didn’t have time, so he read Claire Tomalin. His weight dropped so fast he looked like an immaculately turned out ginger lollipop. There was a day when he didn’t want to drive anymore, and the Lexus he had treated himself to sat outside, forlorn. There came the day when Mark the window cleaner came to see him, and Mark cried as he was leaving, and still cleans our mother’s windows for the same price as when our father died. Nine pounds, sterling, the whole house. Dad’s best mates turned out in a borrowed mobility people carrier to take him out for what was obviously their last lunch and I got Dad rigged out in full pomp and we are standing on the front step, him on a silver topped cane, watching them trying to do a 3 point turn and Dad said to me, ‘I’ll be dead before they’ve managed this’.

It seemed impossible that he would die in six weeks, yet he did. Almost as if once he knew it was a race to the finish line, with himself.

Then came the pyjama days, sitting on the settee, talking. Going through old photos. There was a photo of Dad crying laughing over who knows what? He said, offhand, ‘Remember me like that’. I sat back, starting to cry, the tears nearly bursting out of me. He turned on me and bonked me on the forehead with a closed fist.

And he said, ‘Don’t you DARE feel sorry for me. I have lived an extra-ordinary life. Promise me that when you are where I am now, that you will be able to say the same’. Then he tried to light one of his beloved cigarettes and the lighter wouldn’t play, and he said, ‘Will nothing hurry this fucking cancer up’.

He had an incredible nurse called Penny, who he loved. At the end she would give him a wet shave to ‘stay smart’, and stroke his hands and feet. Then lay on the bed with him. He felt so cared for.

He was so brave. He lost his mind for a bit, in the last week, raving, and then, the famed sudden lucidity, and he was looking at me and I said, What? He said, ‘I am leaving this world two beautiful daughters. Can you imagine having ugly daughters? Unacceptable.’

Right at the end, the noise of children playing outside disturbed him so I asked them to be quiet. Dad died at four minutes past midnight that night. Our GP came in his tracksuit to confirm time of death, and then I washed and dressed my father in his super new death pyjamas and dressing gown. The family undertakers (they do all of us) came to take him away at about 3. It was summer, and warm. As he was driven off I shouted, ‘Bye Dad, Bye!’ and waved, feeling the abyss of grief open beneath me. Then I found that the village children had strewn their school sunflowers, and wheat and barley and grass from the fields all over the bonnet of his car.

Dad was sent off with a huge bundle of sunflowers, wheat, barley and grass on his coffin. Some people said the choice of flowers was strange. They still ate the free sandwiches.

Now, as I look at my mad life, I miss my father immensely because I think he would have enjoyed it. Our mother always says he would have hated being old, and I think he would have done. He wasn’t made for old bones, but I am glad he knew and loved Mr I. Mum keeps Dad’s ashes in the book case, and talks to him. He’s furious about politics at the moment. I am eternally grateful for giving me the will, and the belief, to live an extraordinary life. Our father’s life was short, but it has left a lasting legacy in this world. He must have listened to the black box of the Concorde crash in his study way more than a hundred times, and I took him a cup of tea and he was crying. We listened to it together one more time, and I will never forget that for the rest of my life. 9/11 was top secret, so he disappeared into his room for days, the phone ringing all the time. At that Christmas dinner, he was preoccupied, and jumped up to go and find something in one of the endless printouts.

When he died I thought I should post something on one of his aviation forums, as he never said he was dying. ‘I’m sorry to announce…’ And it came back with RIP A Legend, then just copied and pasted hundreds of times by people all across the world. His work lives on. When you get on a plane, or look up at the board, that is our parents. Designed by dad with a marker pen on our formica kitchen cupboards. Modern air traffic control. With our mum applying tea, scotch, and cold towels to his head and making the fax machine work.

Yesterday, a friend I have met since who is Jordanian air force sent me a video of himself doing a glory roll in his jet over Petra, where we were together.

I will live an extraordinary life. I already have. I mean, I’ve already been to a wedding in Athens dressed as Live Aid Freddie Mercury with a rainbow glitter moustache. I was Book of the Week on R4. I’ve got a mate that inverts his jet over Petra for fun. I live with Mr I, an absurd sausage dog called Whitney Houston, and now Barry the Bat.

Live extra-ordinary lives, pals, it’s where it’s at.